Germany’s

Jewish Knights of the Air

by Robin D. Smith of WPAFB

Introduction

During World War I warriors took to the skies for the first time in history. People of all nations were enthralled by the courage and daring of young men who were determined to fly despite primitive aircraft, insufficient training, physical hardships, and enemy fire. The fighter pilots were looked upon as “knights of the air” because they had a reputation for a certain amount of chivalry, especially compared to the soldiers on the ground. The essence of chivalry is recognizing the common humanity of our enemies, and treating them with as much dignity as wartime allows; chivalry puts boundaries and limits on cruelty and destruction during the waging of war. It is based upon Biblical principles, especially those expressed in Isaiah 1:17: “Make justice your aim; redress the wronged, hear the orphan’s plea, defend the widow.”

Many people have heard of famous World War I pilots such as America’s Ace of Aces Eddie Rickenbacker or Canada’s Billy Bishop, and even more have heard of “The Red Baron,” Germany’s Manfred von Richthofen. Most people are not aware that Germany also had many Jewish fighter pilots, at least 135 whose names we know, if nothing else. A few of those brave men are commemorated here.

Acknowledgement

We have Felix A. Theilhaber, a Berlin physician, to thank for most of what we know about Germany’s Jewish fighter pilots. Theilhaber served with distinction as a doctor in the German Army during World War I, and was dismayed to constantly hear in the media that Jews were not doing their part in the war effort. He was especially dismayed to hear  that there were no Jewish fighter pilots because Jews were too cowardly to fly; he knew this was a lie and was determined to set the record straight. In 1916 he wrote a book called Die Juden und der Weltkrieg (The Jews and the World War). In 1918 he wrote Jüdische Flieger im Kriege (Jewish Flyers in the War) and revised it in 1924 as a volume called Jüdische Flieger im Weltkrieg (Jewish Flyers in the World War), in which he gave accounts of over one hundred Jewish soldiers who flew for Germany. The book was coldly received in Germany, and Theilhaber had a difficult time trying to advertise it or sell it.

that there were no Jewish fighter pilots because Jews were too cowardly to fly; he knew this was a lie and was determined to set the record straight. In 1916 he wrote a book called Die Juden und der Weltkrieg (The Jews and the World War). In 1918 he wrote Jüdische Flieger im Kriege (Jewish Flyers in the War) and revised it in 1924 as a volume called Jüdische Flieger im Weltkrieg (Jewish Flyers in the World War), in which he gave accounts of over one hundred Jewish soldiers who flew for Germany. The book was coldly received in Germany, and Theilhaber had a difficult time trying to advertise it or sell it.

In 1933 the Gestapo arrested Theilhaber for the research he was doing in the field of reproductive science. After his release he decided to immigrate to Palestine. In the midst of World War II he founded Kupat Cholim Maccabea Health Services. Today a wing of the Maccabea Health Services office building in Israel bears his name.

WILLIE ROSENSTEIN

Willie Rosenstein was a World War I ace and a pre-war aviation pioneer. He was born in Stuttgart on January 28, 1892. Because he had a keen interest in engines and cars, he decided to become a motor engineer. In 1912 he earned his pilot’s license (No. 170) at the famous flying school at Johannisthal. Soon afterwards he became a flight instructor, a test pilot, and a contestant in airplane competitions. His great flying talent made him nationally known. When war was declared in 1914, Rosenstein volunteered for duty as a pilot. At first he piloted two-seaters: while he flew the plane, another man would observe the enemy below. Later in the war the observers were armed with machine guns and participated in air combat. Pilots of one-seaters had both jobs of flying and shooting, and Rosenstein eventually became the pilot of a one-seater. From February to December 1917, Rosenstein was a member of Jasta 17, which was under the command of Lieutenant Hermann Goering. (Jasta was short for Jagdstaffel, or squadron. It was part of a Jagdgeschwader, or wing.) Rosenstein had his first confirmed aerial victory while in Jasta 17. In late 1917 an incident occurred in which Rosenstein became very upset after Lt. Goering made an anti-Semitic remark in front of several people; Rosenstein requested an apology but when Goering refused, Rosenstein asked for a transfer out of the unit.

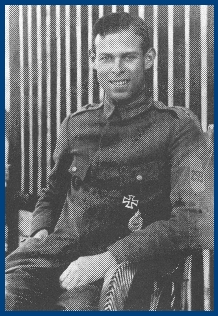

In Rosenstein’s official assessment, Goering wrote that Rosenstein was a fine pilot but that he was suffering from nervous exhaustion, and for a short while Rosenstein was assigned border duty. He eventually was transferred to Jasta 40, led by Lt. Carl Degelow, and Rosenstein flourished under his command. Rosenstein shot down several more enemy aircraft and was even made Deputy Staffelführer (squadron leader). Rosenstein always received excellent assessments from Degelow. Rosenstein received credit for shooting down seven enemy aircraft (shooting down five or more made you an “ace”), but he most probably deserved credit for two additional victories. His last two victories occurred near the end of the war and as a result, his claims were never officially processed. Among the decorations he received for his wartime service were the Iron Cross (First Class), the Order of the Zaringer Lion, and the Württemburg Service Medal in Gold.

Because World War I was so long ago and because of the Holocaust, photographs of Germany’s Jewish fighter pilots are very rare. We are very fortunate that three photo albums belonging to Willie Rosenstein still exist. Rosenstein’s photos and personal papers are part of the Robert B. Gill Collection, and Mr. Gill has generously allowed us to include here several photos from Rosenstein’s photo albums:

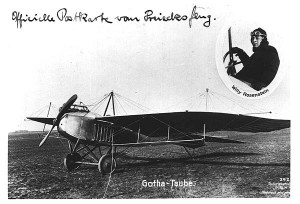

Rosenstein was commemorated as an aviation hero on this 1912 German postcard.

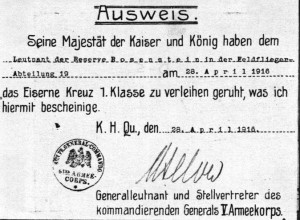

The document announcing the award of the Iron Cross, First Class, to Rosenstein for the heroism he displayed after he and his observer were hit by enemy fire. Because of his courage and outstanding flying skills, Rosenstein was able to get their aircraft safely home. Rosenstein spent over a month in the hospital recuperating from his wounds.

Fooling around in the officers’ club of Jasta 40. The guns are pointed at squadron leader Lt. Carl Degelow. Rosenstein (front row, second on the right) doesn’t seem very amused.

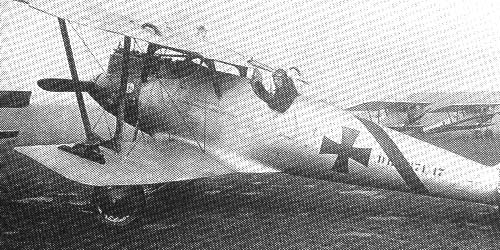

Rosenstein poses on top and in the cockpit of his Albatros D.III in 1917.

Rosenstein kneels like a knight of old, while an admiring lady presents him with victor’s laurels.

Rosenstein’s white-hearted, black Fokker D.VII

(For more on Willie Rosenstein, see the “After World War I” section below.)

WILHELM FRANKL

Wilhelm Frankl is the most well known German Jewish fighter pilot of World War I. He was born in Hamburg on December 20, 1893, and his family later moved to Frankfurt-am-Main. After graduating from school, Frankl went to Germany’s famous aviation center at Johannisthal and took flying lessons from Germany’s first female pilot, Melly Beese. After the war started he volunteered for the air service and proved to be an outstanding fighter pilot. In 1916 Frankl became engaged to the Christian daughter of an Austrian naval officer, and he made a controversial decision to convert to Christianity. Some say he converted to please his future wife, while others say he converted in the hope that he would have better career opportunities. (Jews in Germany were not allowed the same rights as Christians.)

German postcard from World

War I honoring Frankl

In a short amount of time Frankl shot down several enemy planes, and soon afterwards his picture was featured on German postcards and he was hailed as a national hero. Frankl received the Pour-le-mérite (nicknamed the “Blue Max”), which was Germany’s equivalent to America’s Medal of Honor. He was made commander of his own squadron, Jasta 4.

Frankl was killed on April 8, 1917, when the Albatros D.III he was flying fell apart during combat over France. Just three days before he had shot down three enemy aircraft in one day, for a total of 19. He was buried in Berlin-Charlottenburg, but his grave has been lost to war and history. Frankl was excluded from Pour-le-mérite Flieger, Walter Zuerl’s 1938 chronicle of German World War I fighter pilots who had received the Pour-le-mérite. In spite of his conversion, Frankl apparently was, in Nazi eyes, still a Jew.

In 1973 the German Luftwaffe named a squadron after him.

FRIEDRICH RÜDENBERG

Friedrich Rüdenberg was born in 1892 in Hanover. As a young man he studied to become an electrical engineer, and he had just finished his courses and was preparing to take his state exams when the war started. Rüdenberg postponed his education and volunteered for duty. He applied to an aviation detachment and after completing the basic training started going on reconnaissance missions. He collected valuable data and was awarded the Iron Cross in mid-1917. Because of his excellent record, he was selected for fighter pilot school and after his training was assigned to Jagdstaffel 10, under Richthofen’s wing command. Toward the end of the war he was allowed to complete his education, and after the war he taught for several years at the university level. He eventually was made Technical Director of the Istanbul branch of General Electric, but in 1936 he was dismissed from his job because he was Jewish. He wisely decided not to return to Germany but instead immigrated to Palestine.

Rüdenberg in the Cockpit of a Pfalz D. III

FRITZ BECKHARDT

Fritz Beckhardt was from Wallertheim in Hesse. At the start of the war he volunteered for the infantry and later trained as a pilot in Hamburg and Hanover. He flew long-range reconnaissance missions and later received fighter pilot training and served with Jagdgeschwader 3, Jagdstaffel 26, and Kest 2. During the war Beckhardt received the Iron Cross (First Class), the House Order of Hohenzollern with Swords, the Hessian Medal of Bravery, the Hessian Order of Ernst Ludwig, the aviator’s badge, a silver cup for bravery, and various badges for accomplishments and wounds. After Germany lost the war, Beckhardt refused to deliver his plane over to the enemy and instead flew it to Switzerland.

Beckhardt flew a Siemens Schuckert fighter with a swastika on it. Pilots on both sides flew planes adorned with swastikas, an ancient symbol that at the time of World War I still represented the sun, or good luck, or just an interesting image.

BERTHOLD GUTHMANN

Berthold Guthmann (left) with his sister and brother

Berthold Guthmann was born in 1893 and had just started his university studies when the war started. He volunteered for military service, as did his two brothers (one of whom was killed at Verdun). He became an observer and gunner on military aircraft and received the Iron Cross (Second Class), the Tapferkeitsmedaille (Medal for Bravery), and the Verwundetenabzeichen (the German equivalent of the Purple Heart). After the war he became a prominent attorney in Wiesbaden. In addition to being the secular leader of the Wiesbaden community during its most difficult years (1938-1942), Guthmann was second in charge of the Frankfurt Jewish congregation during its final months (1942-1943).

AFTER WORLD WAR I

“Now the present troubles touch me deep in my heart.

A wish becoming unified, a single sacred longing,

An inspiration. Jews and Teutons—

That we are German, no proof is needed.

Because the Jews of their own volition gladly

Rally around the flag of their Fatherland.

For me to gain—be it, if it falls to my lot,

Even with my own blood—the Fatherland,

Which to myself and my brothers, alas, alas,

Often has been a Stepfatherland….”

Immanuel Saul (Translated by Adam M. Wait)

Immanuel Saul was a Jewish soldier in the German Army who was killed in World War I. Saul yearned in the poignant lines of his poem to finally gain Germany, even with his own death, as his Fatherland. Saul had hoped that the fact that so many Jews were willing to lay down their lives for Germany in World War I would inspire the nation to finally recognize and reward their longsuffering devotion. It would never happen.

Jews and Communists were blamed for Germany losing the war. After the Nazi party came to power in Germany, Hitler immediately set upon making life as difficult as possible for German Jews. He first did this through anti-Semitic legislation designed to isolate Jews from the rest of society. Fritz Beckhardt, the Jewish pilot who had flown in World War I with a swastika on his plane, was imprisoned in a concentration camp because of his relationship with an “Aryan” woman. His old flying comrade, Berthold Guthmann, boldly appealed to Hermann Goering, Hitler’s right-hand man, as a fellow flier and asked him to intercede on behalf of Beckhardt. Although Goering was the creator of the concentration camps (and the Gestapo), he granted Guthmann’s request and released Beckhardt, who then left the country.

Hermann Goering as a World War I fighter pilot

After Hitler came to power, Willie Rosenstein found it difficult to fly. The Nazis made it very clear that he was not welcome at any flying fields. An old war comrade was in charge of one of the flying fields, however, and he refused to comply with Nazi orders that Jews were forbidden to fly. He allowed Rosenstein to use the field whenever he wished, but Rosenstein became concerned that his old comrade would soon get into serious trouble, so he stopped going to the flying field. Rosenstein decided that he and his family should get out of Germany, and although the Nazis did not want Jews in the country, they made it increasingly difficult for Jews to leave. When German Jews tried to emigrate, the government taxed so much of their money and property that in most cases there was not enough left to buy a passage to another country or to provide a means for making a living. Rosenstein was running into all kinds of Nazi bureaucratic roadblocks as he tried to leave the country. A man Rosenstein had barely known from his days in Goering’s squadron told Rosenstein he would inform Goering of his dilemma. Considering the circumstances under which he had left Goering’s squadron, Rosenstein expected no help. To Rosenstein’s great surprise, Goering sent him a letter that he admits “made things easier in some ways,” because he was allowed to leave the country and take three planes and their spare parts with him, “a privilege which was not granted to other Jews at that time [summer 1936].”

Berthold Guthmann once said that Richthofen was like “an umbrella that gave all the German pilots a covering of fellowship and chivalry,” and Hermann Goering, in the case of Rosenstein and Beckhardt, was loyal to the brotherhood of fliers.

Unfortunately, a new kind of chivalry was rising up in Germany, one that was being developed by Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler. Himmler was obsessed with tales of knights and Camelot, but he wanted a uniquely German brand of chivalry. In the First World War, Richthofen had described the chivalry of fliers as: “A chivalrous battle with similar weapons, each with a machine gun and an airplane, some athletic ability and: only the heart remains to be weighed.”

Himmler’s knights would have no heart; they would glory in showing no mercy and no fairness. Himmler wanted a chivalry stripped of Jews and Jewish values. Medieval chivalry had been based upon Biblical principles of mercy and defense of the weak, especially women and children. Old Biblical principles had to be done away with if Nazi knights were going to fulfill their mission of killing the weak and defenseless. Ironically, Jewish values were removed from ideals of German chivalry in order to make it easier for Germany’s new knights—the SS—to destroy the Jews.

Manfred von Richthofen, also known as the “Red Baron,” was rumored by some to be of Jewish descent.

Berthold Guthmann had served Germany faithfully in its fledgling air force during World War I, but that made no difference to the Nazis. He was not seen as a German, a veteran, or a human being. In 1943 Guthmann and his family were arrested, split up, and sent to various concentration camps. Although Guthmann had saved Beckhardt’s life a few years earlier through his plea to Hermann Goering, no one interceded on Guthmann’s behalf, and he was killed at Auschwitz as if he had been nothing more than an insect.

The gates of Auschwitz

Ironically, when Theilhaber wrote his book on Jewish fliers in 1924, he lamented at the end the suffering that had already been inflicted upon Jews through the symbol of the swastika, which he called “the emblem of all Jew-haters.” He had no idea the worst was yet to come.

Berthold Guthmann and his family in happier, more civilized times.

If you have any information on Germany’s Jewish fighter pilots in World War I that you would like to share with us, please contact us at jewishknights@aol.com.

SOURCES

Badinger, James. “Jewish Quandary,” online at http://judischequandry.tripod.com.

Cook, Stephen, and Stuart Russell. Heinrich Himmler’s Camelot: The Wewelsburg Ideological Center of the SS, 1934-1945. Kressmann-Backmeyer, 1999.

Doerflinger, Joseph. Stepchild Pilot. Tyler, Texas: Longo, 1959.

“Felix Theilhaber.” Online article at http://www2.rz.hu-berlin.de/sexology/GESUND/ARCHIV/COLLTHE.HTM.

Gavish, Dov, and Dieter H.M. Groschel. “Leutnant der Reserve Friedrich Rüdenberg.” Over the Front, Summer 2001, pp 99-132.

Gill, Robert B. “The Albums of Willy Rosenstein: Aviation Pioneer, Jasta Ace.” Cross and Cockade, Winter 1983, pp 289-334.

Keen, Maurice. Chivalry. New Haven: Yale UP, 1984.

Kilduff, Peter. Letter to Robin Smith, Sept. 4, 1996.

Opfermann, Charlotte. The Art of Darkness. University Trace Press, 2002.

Over the Front, Journal of the League of World War I Aviation Historians, online at http://www.overthefront.com.

Pourlemerite.org at http://www.pourlemerite.org/index.html.

Richthofen, Manfred von. “Der rote Kampfflieger.” Ein Heldenleben. Berlin: Ullstein, 1920.

Smith, Robin D. Last Knight, First Ace: The Red Baron as Legend and Myth. Master’s thesis, Wright State University, 2000.

Theilhaber, Felix A. Jewish Flyers in the World War. Trans. Adam M. Wait. N.p., 1988.

Theilhaber, Felix A. Jüdische Flieger im Weltkreig. Berlin: Verlag der Schild, 1924.